Mandibular Fossa Definition

Mandibular fossa is a concavity in the squamous portion of the skull’s temporal bone.

This is the area where the head of the mandible articulates with the articular disk. It allows the mouth to be closed and opened, meaning it exists to perform mastication. Its articular exterior is sheathed by fibrocartilage [1].

Mandibular fossa is separated into two by the petrotympanic fissure. The anterior part is the bigger one and it joins with the mandibular condyle. It extends up to the external acoustic meatus. The posterior part contains a section of the parotid gland [2]. Posteriorly, squamotympanic fissure separates the mandibular fossa to the tympanic plate [3].

What are the boundaries of the Mandibular fossa?

The roof of the mandibular fossa composes of the floor of the middle cranial fossa.

- Anteriorly, the articular tubercle made up of connective tissue is present.

- Posteriorly, it lies in the middle of the squamous and tympanic parts of the temporal bone. It becomes elevated to form the glenoid process then it goes straight to the external acoustic meatus. When you put your fingers into the external acoustic meatus and you chew, you will feel the mandibular condyle moving in the fossa.

- On its lateral side is the tympanosquamous suture which is largely composed as a bony ridge. The zygomatic process lines the lateral side of the mandibular fossa.

- On the medial end is the inferior part of the tegmen. Behind the tegmen is the petrotympanic fissure [4, 5].

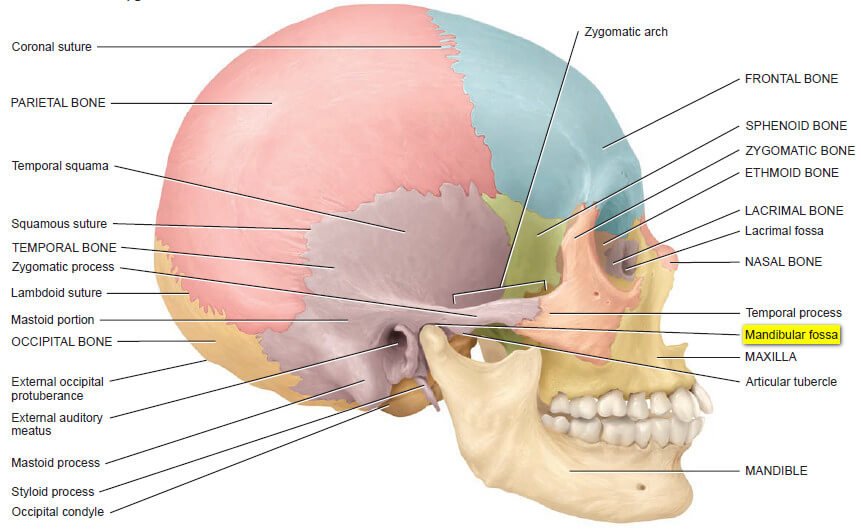

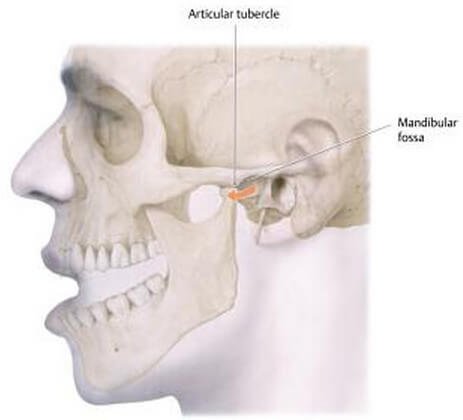

Anatomy (Photos): Where is it Located?

Picture 1: Mandibular fossa is posterior (behind) and inferior (below) to the zygomatic process of the temporal bone. It is posterior to the articular tubercle. The articular tubercle, mandibular fossa, and mandible join together to form the temporomandibular joint (TMJ).

Image Source: Tortora GJ & Derrickson B, Principles of Anatomy and Physiology 12th edition, John Wiley & Sons Inc. 2009, p 204

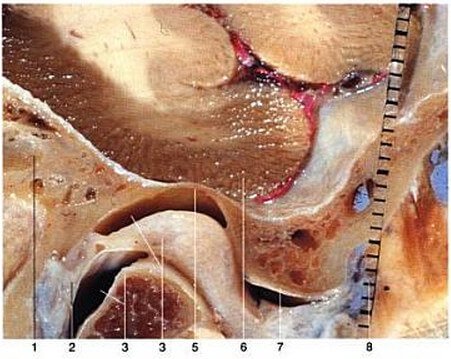

Picture 2: This is the roof of the mandibular fossa that measures 0.1 mm.

1) External acoustic meatus 2) Bilaminar zone of articular disc 3) Mandibular condyle 4) Articular disc and upper joint space 5) Glenoid fossa 6) Temporal lobe 7) Articular eminence

Image Source: Lang J, Clinical Anatomy of the Masticatory Apparatus Peripharyngeal Spaces, Thieme 1995, p 56

Picture 3: Inferior View of Temporomandibular Joint’s Mandibular Fossa

Image Source: Baker EW & Schuenke M, Head and Neck Anatomy for Dental Medicine, Thieme 2011, p 36

Mandibular Fossa Function and its Importance

Mandibular fossa performs a large part in the act of mastication. As a part of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), together with the articular tubercle and mandibular condyle, they become responsible for opening (depression of the mandible) and closing (elevation of the mandible) the mouth, as well as for moving it forward (protraction), backward (retraction), and side to side [5].

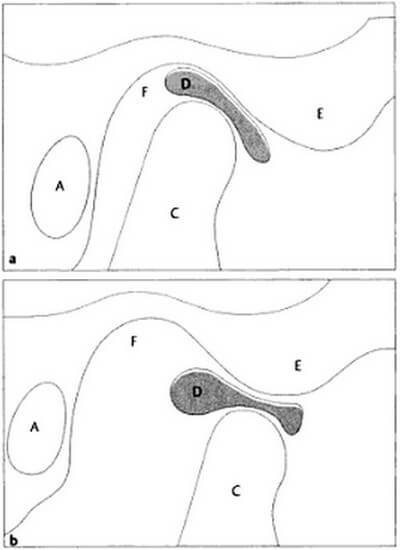

Picture 4: This is the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) when the mouth is a) closed and b) opened.

A) External auditory meatus C) Mandibular condyle D) Articular disk E) Articular eminence F) Mandibular fossa

Image Source: Burgener FA et al, Differential Diagnosis in Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Thieme 2002, p 409

When the mouth is closed (see Picture 3a), the posterior part of the articular disk is at the center of the mandibular fossa and the anterior part of the disk lies inferiorly following the lining of the mandibular fossa. These two, together with the condyle, becomes aligned in a coronal plane.

When you open your mouth (see Picture 3b), the mandibular condyle rotates into the articular surface of the articular disk. This disk-condyle complex goes forward to the articular eminence of the temporal bone [6].

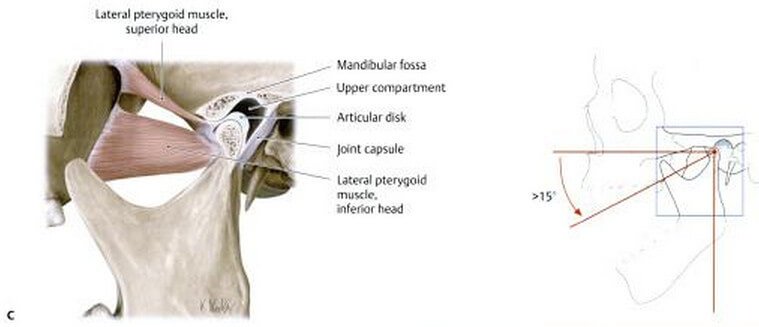

Here is a more detailed illustration of how the temporomandibular parts move in the closing and opening of the mouth. We will concentrate on the part where the mandibular fossa is involved [1].

Picture 5: In a closed mouth, the mandible simply lies on the mandibular fossa.

Source: Baker EW & Schuenke M, Head and Neck Anatomy for Dental Medicine, Thieme 2011, p 35

Picture 6: In this photo, the mouth is opened 15 degrees. Like in a closed mouth, the mandible still lies on the mandibular fossa.

Image Source: Baker EW & Schuenke M, Head and Neck Anatomy for Dental Medicine, Thieme 2011, p 35

Picture 7: When the mouth opens for more than 15 degrees, this is the time when the mandible shifts forward. It is being moved anteriorly by the inferior head of the lateral pterygoid muscle. This muscle’s superior head, on the other hand, pulls the articular disk towards the articular tubercle.

Image Source: Baker EW & Schuenke M, Head and Neck Anatomy for Dental Medicine, Thieme 2011, p 35

Clinical Importance of Mandibular Fossa

Mandibular fossa exists to allow the act of mastication or chewing. Imagine your life if you cannot chew. You’d be miserable. Damage to the mandibular fossa or other anatomical structures for mastication will definitely cause disturbances to your eating patterns, leading to a more serious and complex problems.

The posterior part of the mandibular fossa is non-articular. In fact, the inferior tympanic artery and chorda tympani nerve passes through this area without the danger of being pressed against the surrounding structures. One part of the parotid gland called the glenoid lobe projects into this area of the mandibular fossa. If mandibular fossa is damaged, these structures associated to it might be affected.

Picture 8: Dislocation of temporomandibular joint (TMJ)

Baker EW & Schuenke M, Head and Neck Anatomy for Dental Medicine, Thieme 2011, p 37

Exaggerated yawning and direct trauma to an opened mouth leads to dislocation of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). What happens is that the mandible glides anterior to the articular tubercle. As a result, the mouth cannot be closed. Fortunately, this is easily managed by pressing on lower jaw [1].

References:

- Baker EW & Schuenke M, Head and Neck Anatomy for Dental Medicine, Thieme 2011, pp 35-37

- Gray H, Anatomy of the Human Body, Bartleby.com 2001

- Snell RS, Clinical Anatomy by Regions 9th edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2012, p 532

- Lang J, Clinical Anatomy of the Masticatory Apparatus Peripharyngeal Spaces, Thieme 1995, p 57

- DiGiovanna EL et al, An Osteopathic Approach to Diagnosis and Treatment, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2005, p 607

- Burgener FA et al, Differential Diagnosis in Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Thieme 2002, p 409